Congenital Heart Disease Awareness Week: Art’s Healing Impact on CHD Patients (Part 1)

“When he was recovering from surgery and couldn't quite dance yet, he still wanted to go and watch the class. he was thrilled when he could rejoin.”

Each year, the week leading up to Valentine’s Day marks Congenital Heart Disease Awareness Week, shining a light on the most common birth defects in the United States. According to the American Heart Association, congenital heart defects (CHDs) affect roughly 1% of, or 40,000, births a year, falling into a number of different categories that range from the relatively benign to incredibly severe.

Gabe Greenberg is a nine year old boy from the Capital Region born with such a condition. The official medical diagnosis provided by his mother, Melissa, is Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia and major aortic pulmonary collateral arteries. In layman's terms, Gabe has an extreme combination of multiple heart defects.

“When he was born, we didn't know truly how long he would be with us,” Melissa tells me. “There was so much uncertainty surrounding his diagnosis – what the treatment was going to be and whether he would be able to have his heart repaired.”

Over the course of his short life thus far, Gabe has had three open heart surgeries and at least a dozen cardiac catheterizations in order to keep him functioning as positively as possible. I spoke to his mother on his ninth birthday about what it’s taken for him to understand and persevere through all of the trips to the incredible Children’s Hospital in Boston.

“He actually has a really great understanding of all of it. Because everything was so frequent early on and slowly spaced out over time, he never had a break where he was able to forget that something was happening. He was just very matter of fact about having procedures and, even though he has a brother that doesn't have congenital heart disease, he really thought it was just something all kids dealt with. It was very normal for him.”

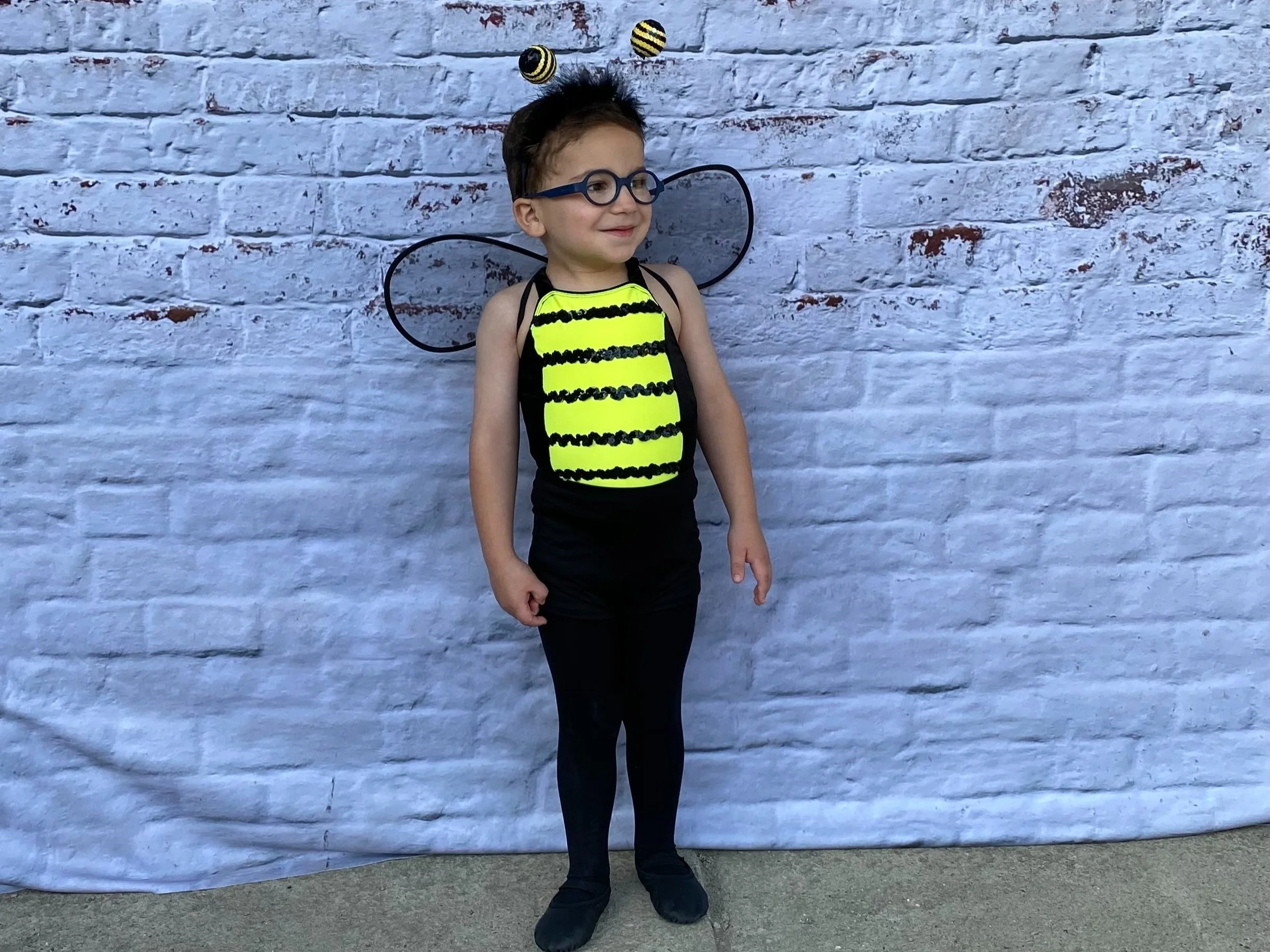

Provided by Melissa Greenberg

Of course, it’s a well-known fact that kids are resilient. You’ll often hear parents claim that harrowing experiences like these hit the parents harder than the kids themselves. For the Greenbergs, persevering was never an option; the whole experience is a testament to the inherent strength we all possess as human beings.

“In the beginning, we were literally living from one procedure to the next, between the cardiac tests and the open heart surgeries,” Melissa reflects. “He just wasn't thriving, and there wasn't even time to sit down and really think about what was happening. But as he's gotten older and things have spaced out, we just look back and go, ‘wow, this was really scary.’ We didn't know how long we'd have with him.”

Living with a condition like Gabe’s makes it more difficult to participate in certain activities and extracurriculars. Most notably, he has a harder time breathing than most and therefore, any cardiovascular activity wears him down. Things that involve a lot of running for example are particularly difficult and unenjoyable. So when his parents enrolled him in dance classes at three-and-a-half years old, it was like finding a missing jigsaw piece.

“We put him in ballet and he just never stopped,” Melissa says. “His dance group has always been very supportive of him and where he's at with his gross motor skills. He did, subsequently, get a cerebral palsy diagnosis on top of everything else, which explains what's going on with his motor skills. But [his class] has always accepted him.”

For anyone with a connection to the arts, it’s undeniable that all forms have healing powers. Perhaps it’s the comforting notions of a relatable lyric in a song. Perhaps it’s a quiet place to slow down and paint a landscape. Or perhaps finding a rhythm – both literally and figuratively – in a group of like-minded peers at a dance studio.

“[Gabe]'s never going to be like a top runner; it’s just not something that he enjoys doing. It's very hard on him, and he tries his best, but he doesn't have the same problems in dance. He can get through two hours of dance classes; sure, he's tired at the end but it's not the same as running on a soccer field for 30 minutes, right? It's a different kind of activity, and it's more suited to what his body can tolerate.”

Since beginning ballet shortly after he could fully walk, Gabe has been lucky enough to experiment with many different types of dance, allowing him to explore the artform and find what best suits him. However, even that has come with its own unique set of limitations.

“Not long after he started dancing, everything shut down with COVID,” Melissa recalls. “It was a very slow re-entry into society for him, just because of the risks. We're definitely to the point where we’re branching out and doing more things but, you know, winters are hard. We have to stay away from a lot of crowded places, especially when everything's been so bad with the flu and everything.”

Provided by Melissa Greenberg

In addition to his three dance classes a week at Barbara’s School of the Dance in Delmar, Gabe has also found a kinship with musical theatre. He and his brother enjoy going to local school plays and they hope to see something on a larger scale together soon.

Melissa expects that having these interests will help Gabe participate in school-based extracurriculars like musicals as he grows up. Having the support of both his dance classmates and other cardiac kids he’s met through the American Heart Association has even further compounded his joy for the artform, and the impact it’s had on his quality of life.

“When he was preparing for the surgery he had at seven, his dance class was very aware of what was going on with him, and the fact that he was going to have to take a break from dance. When he was recovering from surgery and couldn't quite dance yet, he still wanted to go and watch the class. And he was thrilled when he could rejoin.”

Congenital Heart Disease Awareness Week aims to highlight the most common cause of infant death due to birth defects. Patients like Gabe with CHDs “face a life-long risk of health problems such as issues with growth and eating, developmental delays, difficulty with exercise, heart rhythm problems, heart failure, sudden cardiac arrest or stroke.” (1)

But, if there’s one thing Melissa wants people to remember, it’s that a person’s condition does not define them, and it’s important that they have the same seat at the table as anyone else.

“Congenital Heart Disease is something you deal with for your entire life. You’re always a congenital heart patient if you’re born with a defect. These children, they need lifelong care with specialists. They may have some less than typical development along the way, but it’s important that they be immersed in normal kid activities so they can live life to the fullest.”

The resources below are devoted to researching congenital heart defects, each contributing – and dedicated – to making significant strides in increasing survival rates as a result.

The American Heart Association: https://www.heart.org/en/affiliates/new-york

Mended Hearts: https://mendedhearts.org/

The Children’s Heart Foundation: https://www.childrensheartfoundation.org/

CHD Coalition: https://chdcoalition.org/

(1) The Children’s Heart Foundation, https://www.childrensheartfoundation.org/about-chds/chd-facts.html